Negative Behaviors with Autism: Why it Happens and Eight Ways to Help

Mo Buti,M.Ed-BD, M.Ed-ADMIN, QUIP, an advocate and instructional expert for people with autism, was on the case. First, she thoroughly evaluated the situation, exploring each of the possible reasons for that student’s behavior, many of which are included in the list below. Then, once she’d discovered the “why” behind the behavior, she was able to implement a tried-and-true solution, sourced from her 31 years of experience working with people on the spectrum.

And voila! The boy’s mysterious behavior stopped.

Why Negative Behavior with Autism is Prevalent in Classrooms:

It’s a way of communicating.

People on the autism spectrum embody a huge range of communicative abilities, from non-verbal to hyperverbal, but according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, a diagnosis of autism indicates “persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction.”

Unfortunately for educators, practitioners, peers, and learners with autism, physical expression as communication or as an expression of anger can result in harm to property and/or people. Aggression itself isn’t a characteristic of autism, but it can be a by-product of frustration, overwhelm, or lack of communication skills.

It could be a sensory issue.

Bright lights. Loud noises. A shirt tag. Too-tight shoes. Too hot, too cold. People with autism are often either hypo or hyper-sensitive to sensory input. Little things we may not even think about as neurotypicals can throw off an entire day, an entire week, an entire school year for a learner with autism

They need "Stimming."

It’s easy to accidentally reward negative behavior.

They miss social cues.

Change is hard.

They’re bored.

People with autism can be deeply literal.

Autism Classroom Strategies to Address Negative Behavior

1. Observe: Try putting yourself in that child’s shoes (or, if you’re a literal person, look at the situation as if you were inside their body and experience). This can be really tough if you’re an educator in charge of an entire classroom! In this case, Mo suggests:

- Video observation! This is a great option because it allows us to look at how the child responds to our own behavior and instruction. Typically, consent should be obtained from families prior to setting up the camera.

- Grab a substitute for a few hours.

- Switch places with a paraprofessional.

2. Visual Supports: When the world around you is a smorgasbord of sensory input that you struggle to synthesize, visual supports can go a long way in focusing attention, clearly communicating expectation, breaking down tasks, smoothing transitions, and preparing autistic learners for changes to the schedule.

3. Offer opportunities for stimming: As we mentioned above, stimming is important to autistic individuals’ sensory integration, but if it disrupts an entire classroom’s ability to learn or hurts someone, these safer less-disruptive substitute behaviors can help.

Less-disruptive alternatives include:

- Creating a safe space in the classroom for stimming.

- Offering pinwheels for blowing.

- Providing handheld fans to hold.

- Yoga-ball seating (Bungee-cord seat belts can work for flailing bouncers! Just make sure they’re loose enough as to not be restraining).

- Offering thinking putty or beeswax to keep their hands busy (important to consider sensory aversions).

4. Engage learners with autism with the right learning materials: When any child is focused and fully engaged in learning, the need to resort to negative behaviors decreases and motivation to communicate thoughts, ideas, and answers increases.

5. Direct, respectful, age-appropriate language, instruction, and clear boundaries: Ensuring that our communication and instruction is as crystal-clear and direct as possible can be super helpful for learners with autism. Think like a literal person: does the instruction “show your work” really convey the task we are hoping they complete? Think like a person who doesn’t understand body language or subtleties: are we becoming frustrated because they don’t stop talking when we imply that we’d like them to stop?

6. Robust, individualized communication strategies: When someone has a system to communicate and feel understood, it can reduce a lot of negative behaviors that are ways of communicating either needs or emotions.

7. Offer a quiet space to decompress: If a child is constantly running from the classroom or covering their ears, offering a space that feels private and limits sensory input, like a room or a teepee, can go a long way in helping the child self-regulate.

8. Give learners a thinking cap: Okay, so remember the kindergartener that emptied the cubbies in search of a thinking cap? Mo walked over to the dress-up center, located a hat, and plopped it on that kindergartener’s head. And guess what? He stopped emptying cubbies. Creative solutions like this are an awesome and fun way to support learners with autism.

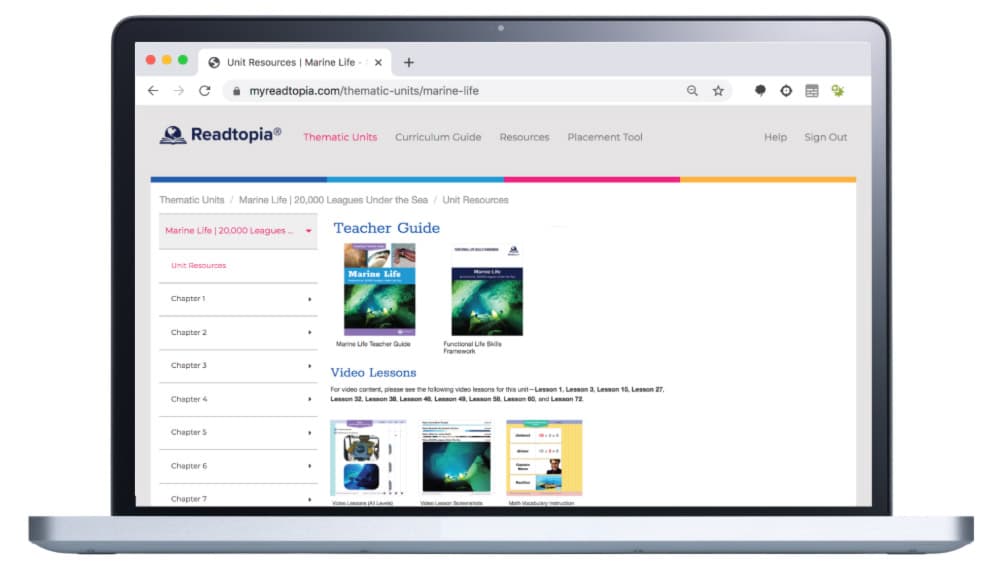

At Building Wings, a team of passionate advocates, practitioners, and educators work together to create engaging and accessible learning materials for learners of complex needs, like autism. These materials save special educators from the task of having to create and adapt their own learning materials.

That something is Readtopia, and since its inception, we’ve heard many anecdotes from teachers and practitioners about learners who’ve traditionally been hesitant to communicate who have been so moved by the very same stories that have inspired generations that they participated in class discussions independently for the first time.

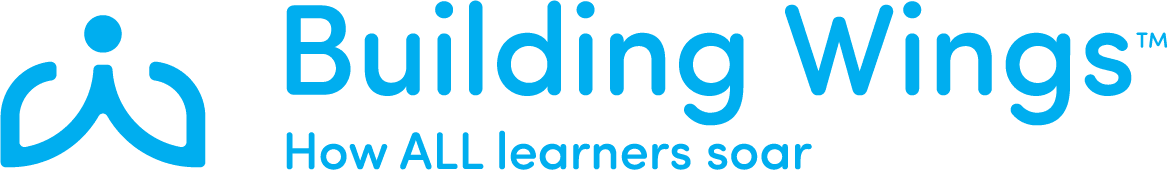

We hope that Readtopia’s instructional guides, age-appropriate materials, and leveled graphic novels included in SEL-focused units like Empathy, Grit and Kindness (anchored by Anne of Green Gables), Working Together (anchored by The Gold Bug), Life Lessons (anchored by Aesop’s Fables), and Values and Responsibilities (anchored by Black Beauty) can serve both the learner with autism and the special educator as a vehicle to engagement, helping to reduce some of those negative behaviors and therefore making learning more accessible to everyone in the classroom.