The Science of Reading

What it is and what it is not

What is the science of reading?

It depends on who you ask. If you follow education websites and related social media feeds, you may encounter references to the science of reading. How people use or define this term–in conversation, legislation, or even in daily instruction–varies. In general terms, the science of reading refers to the large body of research that reflects what we currently understand about how we learn to read.

Some people refer to the science of reading as the skills necessary for reading as well as the challenges people face when learning to read. Others use it to refer to the neuroscience behind how the brain processes written words, which they believe should inform how reading should be taught. Though the education field hasn’t yet reached a consensus about what the science of reading is, most educators and researchers do believe that the kind and quality of reading instruction provided impacts not only a learner’s academic performance, but also their potential to participate and perform within society.

As The Washington Post summarizes, there is “science” underlying just about everything we do. The science behind baking is chemistry; the science behind billiards is physics. Identifying these associations is informative, but it doesn’t necessarily tell us how to help others become better bakers or pool players.

The same goes for the science of reading as it relates to literacy instruction. Further, whenever we call something ‘science,’ we tend to diminish the debate around it because of its factual truth. This can be impactful when it comes to something as important as helping all children become readers.

Science of Reading in the News

Much of the initial press about the science of reading originally stemmed from reports from a community in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania indicating some initial and significant (but unfortunately unsustained) literacy gains for students that resulted from a phonics-intensive approach.

Today, the science of reading is increasingly finding its way into headlines as 29+ states have passed bills requiring more concrete and consistent recommendations for the literacy curricula schools adopt. The science of reading has also infiltrated local or municipal concerns, as many school boards are increasingly requiring some level of compliance.

In actuality, the conclusions one can reasonably draw from the science of reading closely follow those indicated by the National Reading Panel which convened more than 20 years ago. These recommendations include:

- Explicit instruction in phonemic awareness and phonics

- Opportunities for vocabulary development

- Methods to improve fluency

- Ways to enhance comprehension

Is the Science of Reading a Buzzword?

In a recent article, Education Week described the phrase as a buzzword and explored why reading instruction is so challenging to put into practice. The term has also been used to imply that decoding should be the singular focus of reading instruction.

What it is Not

While there may be no one definition for the science of reading, many, if not most people, agree that effective instruction is predicated on the individual and their age, ability, and history.

This means that there is no one instructional panacea for supporting all children. Likewise, the conversation surrounding the science of reading rarely includes or considers the needs of emergent literacy learners, where the focus might be on phonemic awareness rather than phonics, for example, and/or those with low-incidence disabilities who may show gains in smaller and sometimes slower increments.

Research Related to Effective Reading Instruction

The National Reading Panel outlined studies that recommend 90+ minutes of reading instruction per day with comparable amounts of time dedicated to phonemic awareness and phonics, reading comprehension, vocabulary development, and reading fluency. Further research since these guidelines were published have led to additional recommendations including the role of writing in reading instruction.

Notable researchers in this field include Chall (1979), Yeager Adams (1990), the National Reading Panel and National Early Literacy Panel, Scarborough, Gough & Tunmer’s Simple View of Reading, Graham & Harris, Erickson & Koppenhaver, and the National Institute on Child Health & Human Development.

An image widely used to explain the relationship between all the components of effective reading instruction is Scarborough’s Reading Rope, in which each strand of rope is interconnected and interdependent on the others.

Top 10 Questions for Adopting a New Curricula

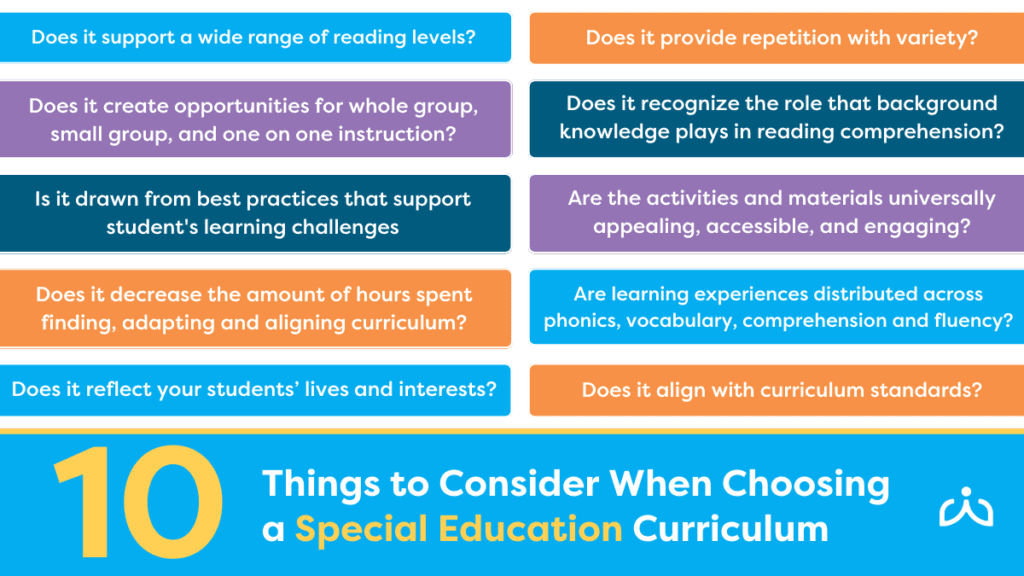

When examining whether a curriculum is aligned to research-supported literacy instruction or the science of reading, consider the following ten questions:

- Does the curriculum support a wide range of reading levels?

- Is the curriculum drawn from best practices in supporting the needs of students who face learning challenges?

- Does the curriculum distribute learning experiences across phonics, vocabulary, comprehension, and fluency?

- Does the curriculum reflect your students’ lives, experiences, and interests?

- Does the curriculum recognize the role that background knowledge plays in reading comprehension?

- Does the curriculum decrease the amount of hours spent finding, adapting, and aligning curriculum?

- Does the curriculum contain activities and materials that are universally appealing, accessible, and engaging?

- Does the curriculum provide the kind of repetition with variety that supports learners in generalizing what they know?

- Does the curriculum create opportunities for whole group, small group, and one-on-one instruction?

- Does the curriculum align with national, state, and grade-level standards, and can you easily demonstrate this alignment to parents, administrators, and others?

Readtopia and the Science of Reading

We are often asked if Readtopia is aligned to the science of reading. The answer is yes.

Readtopia provides daily, sequential, and systematic instruction in the alphabetic principle, phonemic awareness, phonics, and word recognition via the Learning Letters and Making Words supplements. Readtopia also supports vocabulary and oral language development via read-alouds that focus on academic and inferential language. Through guided reading and the exploration of text types and structures, learners have multiple opportunities to deepen comprehension. Focused video segments provide opportunities to build background knowledge and leveled texts help all students participate in independent reading and build fluency. Through repeated but varied exposure to all these experiences, the instruction delivered through Readtopia helps learners weave their skills together to become increasingly independent and conventional readers.

Whether you use the term science of reading or research-based reading instruction, careful examination of the curriculum used for reading instruction is important for the success of learners of all ages, abilities, and levels.